30 Jun Faced with losing her partner, Chloe Hooper turned to stories to talk to her children about death

Jane Messer looks at Chloe Hooper’s recent memoir “Bedtime Story”

The fifth book from Chloe Hooper, an accomplished author of fiction and nonfiction, is in part a bedtime story told across many nights to her two sons, and in part a meditation on how stories – ancient and modern – might sustain or fail us during dark times.

In 2019 Hooper was thrust into a whorl of uncertainty about how and what to tell her children about their father’s very likely terminal leukaemia. Their father is Don Watson, historian, biographer, speech writer and essayist. Out of the blue, he’d been diagnosed with a rare and trenchant form of his disease.

What can you read to help you when your partner might soon be dead, leaving you alone to rear two little boys? Hooper is looking for the “right words”, “an incantation, a spell of hope for the future”. Ostensibly she is reading not for herself, but for her children.

Her eloquent account of this difficult time in their lives is addressed to her oldest boy, Tobias, a vivacious child and avid reader who had recently started school when Don was diagnosed. In this bedtime story, she writes in the second person, to Tobias, but inevitably the reader is placed in the position of the boy; we readers are her “you”.

Rather enchantingly, Hooper imagines them when they’re much older, pulling this memoir and meditation from a bookshelf, rediscovering their lives during what they will later barely remember, their father’s illness and recuperation.

Living hopefully, with death nearby

She imagines they might later be ready for this elegiacal, meditative exploration of living hopefully, with death nearby. “Even going to sleep,” she writes in one of the book’s many instances of expressing the deep connections between life, death and storytelling, “has the old plot line: separation, adventure, return. And each morning is a fresh quest. Sunlight finds its way through the gaps in the drawn curtains.”

The narrative is structured by what she discovers in the books that she reads, the rhythms of family life, and the chronology of Don’s diagnosis, chemotherapy treatment and remarkable recovery. The children steadily grow older. She hands in another book to her publisher. Gabriel is no longer a baby, but a boy with words. A friend’s husband also has cancer, and the friend is shocked to hear that Hooper hasn’t talked to the children yet. Chloe Hooper the mother sometimes flounders, doesn’t know what to say, while Hooper the author writes with aplomb.

She is an honest memoirist: imperfect, struggling, ready to share with the reader how terrifying motherhood can be. Early in the memoir, Hooper acknowledges that turning to stories that might speak to children about loss and death has been the “perfect way” for her to “avoid thinking about the future”. The first problem she faces as a mother is not what to say, but when to start speaking at all.

Hooper turns to myths and legends, epics, the brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Anderson tales. She unearths obscure works such as James Janeway’s A Token for Children, being an Exact Account of the … Joyful Deaths of Several Young Children: “How dost thou spend thy time? Is it in play and idleness, and with wicked children?”

The words with which death, separation and loss have been communicated to children through the ages are key to Hooper’s quest. Were children spoken to differently at times of crisis? Was there something special about the words shared between a parent and a child when only a fire or the moon lit the night? She explores descent narratives, suggesting that humankind’s most reassuring bedtime tale might be that when “our heroes cross to the land of the dead” they “evade death themselves”.

And this uncertainty about whether their hero will cross the river safely is at the heart of Hooper’s terror: that her children will learn about death not through bedtime stories, but first-hand.

She turns to indigenous stories: Mayan, Japanese, Congolese, and Dreaming stories about the Seven Sisters. She reads contemporary narratives, in the much-loved and awarded children’s books that explore loss, illness, absence, separation and death. She reads author biographies, only to discover how many well-known writers for children were themselves orphans, or the child of one surviving parent. After a long time, she concludes that any genre of story will do as long as it resonates, and has “No grand tricks, no showing off.”

Stories of wonder, and catastrophes avoided

Much of the memoir is suffused with images of lamplit darkness: the interiors of the family’s Melbourne home, with the boys being read to at night. Every now and then, a turn of the page brings you to poetry, or short passages that express the filament of a moment, of hope. Hooper imagines other parents and children alone together in the dark, searching – like her – for words, reaching way back in time to before the earliest cuneiform or papyrus, hearing stories in which death, fear and loss are ever-present.

But more present than the past is Hooper with the children, and Don, when he is well enough, telling them his stories. Threaded through the pages are her sketches of Watson’s own childhood in the bush and on a farm, showing how his early life made a storyteller of him. There are also reassuringly ordinary milestones of their family life: the honeyeater that nests in a tree outside their kitchen, and the poignant and witty stories that Watson tells to his boys off-the-cuff at bedtime. Their mother reads to them, their father invents.

At a certain point, Hooper asks Don to use his phone to record his stories, just in case. His stories, some of which she recounts, are about “small-scale acts of wonder”. Once the children know of his illness and the possibility of his death, he invents catastrophes avoided, such as the spider that escapes the home owner’s attempts to rid it from the house and discovers a glimpse of a “brilliant, star-filled sky”.

She realises that she and Don were each raised not to talk about death; “Recognising you’re repressed, however, doesn’t cure you of the affliction.” When Don and Hooper do tell Tobias about his father’s diagnosis, it’s a tense scene, with them sitting separately on the couch while he bounces a balloon.

When Tobias asks, “How do we die?”, Hooper at first deflects. The pragmatic questions continue: “When you die does all your skin disappear?” Ever the reader and writer, Hooper conversationally refers Tobias to a book they have read together about the life of forests and leaf-litter, telling the reader that it’s Henry David Thoreau who wrote that “Leaves teach us how to die.”

By the book’s end, she sees that when she’s best handled her children’s questions, an image or a phrase from one of the stories has been there to support her.

The honeyeater’s chicks survive with the help of the family, as does Don. The thoughts and discoveries Hooper shares with the reader are brilliant, perceptive, healing: “We must all assemble our own paper boats, from old designs or whatever scraps of love and hope are at hand.”

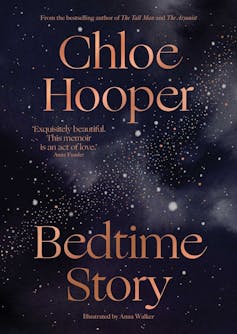

The memoir is illustrated with beautiful charcoal-wash sketches and evocations of forests, leaves, birds and skies. The images are a reminder of the child Alice’s wise words at the start of her Adventures in Wonderland; “what is the use of a book … without pictures or conversations?”![]()

Jane Messer, Honorary Associate Professor in Creative Writing and Literature, Macquarie University

Main Image: Illustration by Anna Walker from Bedtime Stories. (Right) Author Chloe Hooper. Author provided

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.