10 Jun Vale Eric Carle: creator of The Very Hungry Caterpillar, a story of hope … and holes

Vale Eric Carle, by Kate Cantrell and Rhiannan Johnson

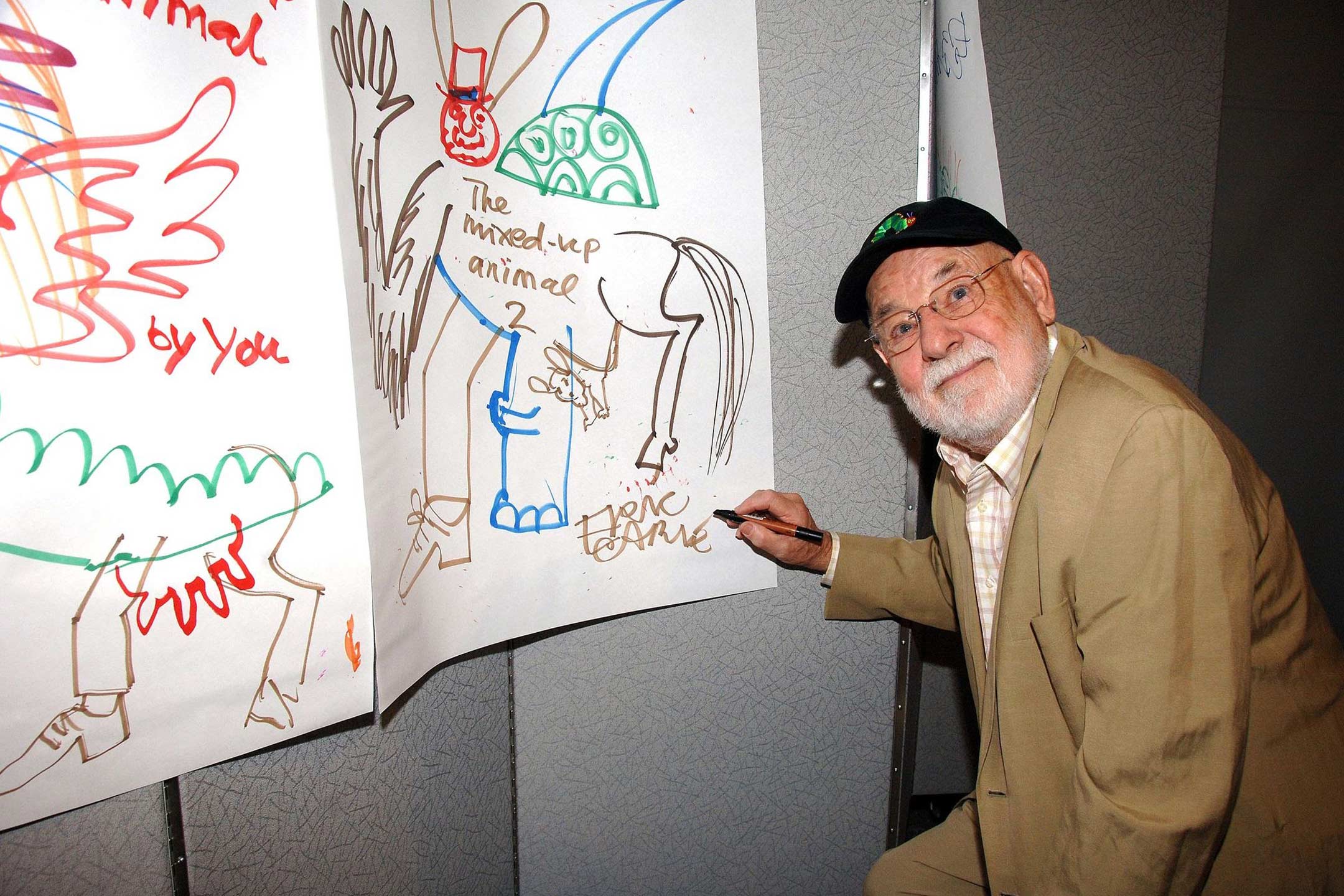

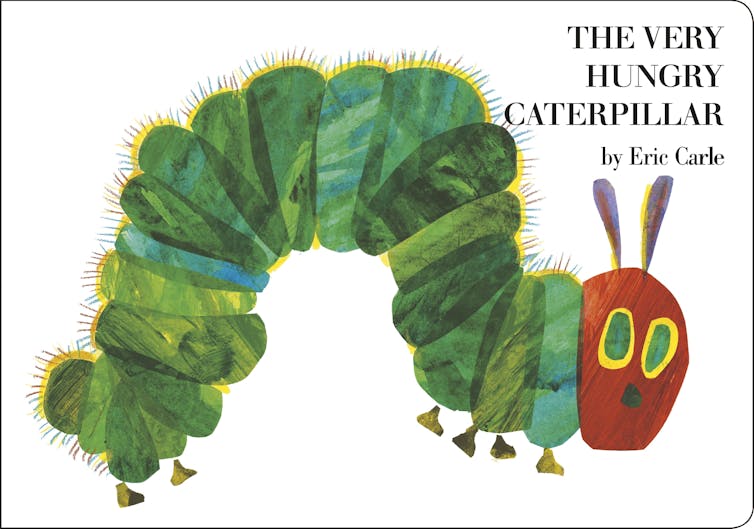

Eric Carle, author and illustrator of beloved children’s book, The Very Hungry Caterpillar, died on 23rd May 2021 — the same day his famous caterpillar is born.

One Sunday morning, the warm sun came up — and pop! — out of the egg came a very tiny and hungry caterpillar.

Described by author Mo Willems as a “gentleman with a mischievous charm”, Carle might have appreciated the irony.

All living things grow and change and die.

But while a caterpillar’s life is spectacularly short, Carle lived for 91 years. He wrote more than 70 books. His most celebrated, The Very Hungry Caterpillar, is frequently cited as one of the best picture books of all time. With just 224 words, it has sold roughly a copy per minute since its publication in 1969.

Growing wings

Despite The Very Hungry Caterpillar’s success, Carle always seemed baffled by the persistent buzz.

In 2014, when asked about the book’s popularity, Carle responded, “I haven’t come up with an answer, but I think it’s a book of hope”.

A decade earlier, he seemed more settled on the idea:

I remember that as a child, I always felt I would never grow up and be big and articulate and intelligent. ‘Caterpillar’ is a book of hope: you, too, can grow up and grow wings.

Remarkably, Carle remained humble. In an interview he gave not long before his death, Carle quietly acknowledged the importance of his work.

“You know, now it’s sinking in,” he said. “It’s taken me a long time to realise, and it is sinking in.”

A glimmer of hope

Like many children’s authors, Carle enlists fantasy to serve the narrative. He speaks to children through animals and insects. In books like Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? (written by Bill Martin) he gives agency to bugs and beetles, and situates the smallest creatures on the same continuum as humans. His work comforts us. The predictable and noncontroversial behaviour of animals is reassuring.

Unlike humans, animals are consistent.

Carle’s caterpillar might be gluttonous, but at least he is true to himself. And he doesn’t apologise for his appetite. He is very hungry, after all.

The book hasn’t been without controversy.

Both George W. Bush and Hilary Clinton read the book to children on their campaign trails — with Bush earning digs for refusing to read any other books, and naming Caterpillar as his favourite children’s book, even though it came out when he was 23.

The American Academy of Pediatrics uses the book as a learning tool to promote healthy eating and educate about the risks of obesity.

A book full of holes

A book full of holes

A child of wartime trauma, with a background in graphic design and advertising, Carle was playing around with a hole punch when he had the idea for a story about a bookworm. The Very Hungry Caterpillar was originally titled A Week with Willi the Worm. But Carle’s first choice of critter was abandoned at the suggestion of his editor, Ann Beneduce, who insisted worms didn’t make likeable characters.

Thus, The Very Hungry Caterpillar emerged, followed by The Very Busy Spider, The Very Quiet Cricket, and The Very Lonely Firefly.

Carle went on to write about grouchy ladybugs, dejected chameleons, even homeless hermit crabs — but never a worm.

Art of wonder

Despite his prolific publishing career, Carle didn’t think of himself as an author, preferring instead the term “picture writer”.

His style is distinct: minimalist text, vibrant illustrations and a multisensory reading experience that moves beyond the simple turning of a page.

The Very Lonely Firefly, for example, includes a set of battery-operated twinkling lights. Mister Seahorse, the story of a fish father who cares for his babies, contains transparent inserts printed with sea environments that can be overlayed as semi-opaque pages.

In Caterpillar, the page width is progressively increased to reflect the quantity of food consumed. Each image of food has a caterpillar-sized hole cutout, as if it has been chomped through.

Ultimately, after some mild abdominal pain and a medicinal green leaf, he transforms into a handsome butterfly.

Carle’s multifaceted practice, combined with his distinctive visual language, transforms his books into objects of wonder and play, lending themselves to repeated readings.

Moreover, while Carle’s images are carefully constructed through technical processes, his work maintains a childlike quality.

His images reflect how children see their world — a series of bold shapes, exaggerated features and fields of moving colour (an effect achieved by collaging on hand-painted tissue).

Indeed, Carle’s bold and bright colours are particularly effective given what we know about the developmental stages of a child’s vision: younger children are better able to perceive and distinguish between bright colours than fainter shades.

Carle called his work “deceptively simple”, a great accomplishment for a man, who — in his words — tried “all his life to simplify things”.

Main Image: Andrew H. Walker

Correction: this article originally included quotes from a 2015 interview published online by The Paris Review. The publication has now stated that the interview was a parody.![]()

Kate Cantrell, Lecturer in Writing, Editing, and Publishing, University of Southern Queensland and Rhiannan Johnson, Lecturer in Visual Art, University of Southern Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.